Latin American Theology Before and After Liberation Theology

For many people, the concept “Latin American theology” primarily brings to mind the liberation theology of the 1970s and 1980s, as if there had not been theological production before or after it. So-called Latin America has been under the influence of European intellectual currents already since the 16th century. In the case of theology, until quite recently it has been mostly Catholic theology.

There is an entire legacy of specifically Latin American thought which has influenced theology that is not well known. A pertinent question for many Latin American intellectuals has been if there is something that could be called Latin American philosophy or thinking, based on a markedly Latin American identity. Independently of the answer to this question, there is a strain of thought that is—at least to some extent—also behind the liberation theology of the late 20th century. Standard presentations on the roots of liberation theology usually ignore this longer and broader intellectual history. It emerged in dialogue with European thought, whether theological, philosophical, or cultural, but is not a mere repetition of it. The question of Latin American culture(s), identity, and history has also long been a critical corrective of Eurocentrism—which for a long time meant the supremacy of Spanish political and economic power, language, religion, and culture.

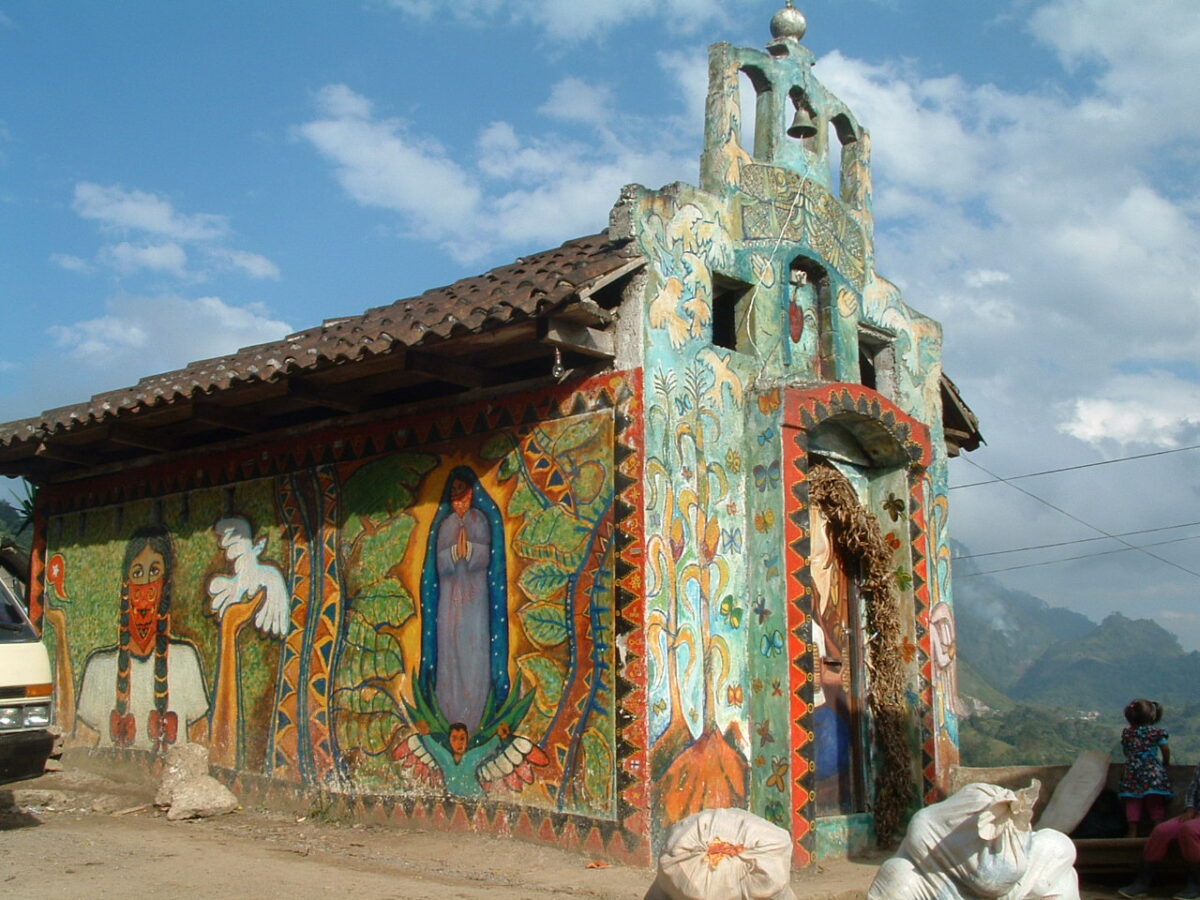

The long, painful, and often violent ties between Spain and America can be observed in different times after the conquest and Christianization of Latin America: for example, during the colonial centuries (15th century to 19th century), the independence struggles of the 19th century, various revolutions—such as the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century, and, closer to our own times, the military dictatorships of the late 20th century. In all these, the question about the legacy and meaning of Christianity has been present, one way or the other.

Even though Latin American theology has become identical with liberation theology, it is important to pay attention to the deep roots of Latin American thought, which also have influenced liberation theology. At the same time, it is as important to note that liberation theology has not died out, as is claimed—often outside the Latin American cultural and linguistic contexts—even though it is not the same as it was at its height. The lively and ever-renewing theological thinking continues to be vibrant in Latin America.

Early Latin American Theology

One of the most well-known early “Latin American” theologians was Spaniard Bartolomé de las Casas (1474/84–1566), “the Protector of the Indians,” who arrived in the Americas as a colonizer but became a Dominican friar and Catholic bishop. His extensive writings on Spanish colonization and dialogue with the Spanish crown influenced both reforms and laws as well as the way the Spanish conquest of America was seen in other European countries. His eyewitness accounts and condemnation of the atrocities against the indigenous populations by the Spanish Christians were always framed theologically. In spite of his general acceptance of the Spanish conquest and especially Catholic missionary work, he can be considered as the first “Latin American” theologian who thought and acted from the specific (cultural, political, economic, religious) context of Latin America. This is the reason why some important liberation theologians, such as Gustavo Gutiérrez, consider Las Casas the “first liberation theologian.” As anachronistic as this claim may be, it is based on the long history of critique of Eurocentrism, the violence of colonization and missionary activities, and interpreting Christianity from the perspective of those who were the objects of forced conversion, subjugation and slavery, the taking over of their lands, and outright violence. Latin American liberation theologians’ way to frame their thinking as pensar desde América Latina (“thinking from Latin America”) rightfully has Las Casas as an early predecessor.

She defended the freedom of thought also in the sphere of religion and theology, criticizing the power of the institutional Church over individual freedom

We could take many other examples of Latin American theological production over the centuries, but for the sake of illustrating the variety and broadness of this history, I will name one: the 17th-century nun, poet, and intellectual, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648–1695) of New Spain, currently Mexico. Her extensive production of poetry and plays, well known in Europe and elsewhere already in her lifetime, made her an icon of both Latin American cultural production and early defense of freedom of thought. Based on her prose, most notably her autobiographical La Respuesta (1691), she could be considered a predecessor of Enlightenment thought in the Americas. She defended the freedom of thought also in the sphere of religion and theology, criticizing the power of the institutional Church over individual freedom. This included an explicit defense of the right of women to think, educate themselves, and express themselves freely. Somewhat similarly as to how Las Casas has been made the “first liberation theologian” by contemporary intellectuals, Sor Juana has been named the “first feminist” of the Americas. Again, in spite of the danger of anachronism, it is clear that her writings present an early line of thought that later was termed feminist. Interestingly, she also learned some nahuatl, a major indigenous language of her time, and wrote Christian narratives into the context of her surroundings, including the indigenous cultures, predominantly in her plays and poetry.

Latin American Liberation Theology Today

Even when direct continuum between Las Casas, Sor Juana, and current Latin American theologians is not drawn, just as in other contexts early intellectuals form an important reference and basis for contemporary theologians. The political importance of liberation theology for the democratization of Latin America has been noted by various scholars. At the same time, in the post-dictatorship context, new social movements emerged. They presented a broader understanding of democracy and the overcoming of the public-private split, but also raised new questions about subjectivity and the rights of such groups as women, indigenous peoples, and sexual minorities. Alongside this, new theologies emerged: feminist, black, indigenous, eco, and gay and lesbian liberation theologies. They all claim the importance of the legacy and influence of liberation theology but go beyond it. They also critique mainstream liberation theology for its blind spots and narrow ways of defining the “poor,” the “oppressed,” and liberation.

Unfortunately, the longer history and contemporary situation of Latin American theologizing is not as well known beyond Latin America as the liberation theology of the 1970s and 1980s. This ignorance also frames liberation theology in a too narrow and stereotypical way. I think it is correct to paint—with a very broad brush—an image of Latin American theology, which has at least the following characteristics over five centuries. First, it takes the cultural, political, societal, economical, and religious context as an explicit reference or starting point, often stemming from the question if there exists some genuinely Latin American thought—or if it is even possible to ask such a question in a meaningful way. Second, because of historical facts, the critique of power is one persistent trait in this legacy—whether that is the colonizers’ power over the Americas, whites over blacks and indigenous peoples, or men over women. Theologically, this includes the critique of the Church from within the Church, as seen in so many other contexts colonized and converted by Europe. Third, the latter point ties Latin American intellectual history to a larger context, today often named the Global South. Latin American intellectuals have over the centuries—and up to our times—dealt with the painful history of European colonialism and Christian missions, which often went hand in hand, aiming at a way of understanding them from the perspective of those who have been their objects. This legacy continues in contemporary forms of Latin American theology, often in dialogue with political science, cultural studies, gender studies, indigenous studies, and economics.

Kirjoittaja

Literature

De Las Casas, Bartolomé (1999). A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Edited and translated from Spanish by Nigel Griffin. London: Penguin. Original Brevíssima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (1552).

Gutiérrez, Gustavo (1993). Las Casas: In Search of the Poor of Jesus Christ. Translated from Spanish by Robert R. Barr. New York: Orbis Books. Original En busca de los pobres de Jesucristo. El pensamiento de Bartolomé de las Casas (1992).

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1994). The Answer/La Respuesta. Edited and translated from Spanish by Electa Arenal and Amanda Powell. New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY. Original La respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz (1691).

Vuola, Elina (2006) “Radical Eurocentrism. The Death, Crisis, and Recipes of Improvement of Latin American Liberation Theology”. In Interpreting the Postmodern: Responses to Radical Orthodoxy. Eds. Marion Grau and Rosemary Radford Ruether. New York & London: T & T Clark and Continuum, 57-75.

Veikko Somerpuro

Veikko Somerpuro