Editorial: Theology from the Global South

Christian theology created in the so-called Global South is not a new phenomenon. It is, however, after the 1960s that self-identified Asian, African and Latin American theologies have come to the fore. They all stress the cultural context, history of colonialism and mission, socio-economic circumstances, and distance from what they consider Eurocentric Christianity.

Changes in Christian churches and post-war and post-colonial societies have also globally triggered new theological thinking. Sometimes these theological currents are situated under the broader umbrella term “liberation theology,” sometimes “contextual theology.” Without going in detail on the differences between the two terms, it is crucial to understand that normative interpretations of the Christian tradition—whether Protestant or Catholic—came under critique from theologians from impoverished and colonialized contexts and from women all over the world.

What had been presented as universal and normative was named as contextual and conditioned. European theology is European theology, which does not naively mean that there are no potential universal elements in it. But it is not only Asia, Africa, or Latin America which form a “context.” When cultural conditions, history, and issues of power are taken seriously also in theology and Christian churches, it is clear that no theology is produced in a vacuum.

This special theme issue of teologia.fi offers glimpses into the diversity of theological thinking in the Global South—here meaning Asia, Africa, and Latin America—areas that share the history and legacy of European colonialism and missions. This is also the first issue of teologia.fi written in English, the lingua franca of global theology today, making also South-South dialogue possible. Latin America is exceptional since the main languages of theological production are Spanish and Portuguese. Already since the 1970s, theologians of the Global South have been in critical dialogue with each other, especially in the context of the Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians (EATWOT), founded in 1976.

Theology from the Global South is as diverse as in any other part of the world. In this issue, we focus on new interpretations, especially in what can broadly be named systematic theology. Theologies from the Global South, including feminist and black theologies, ask critical systematic theological questions regarding such aspects as the image of God and, concomitantly, the human as imago Dei, ethics, the church, and Jesus Christ.

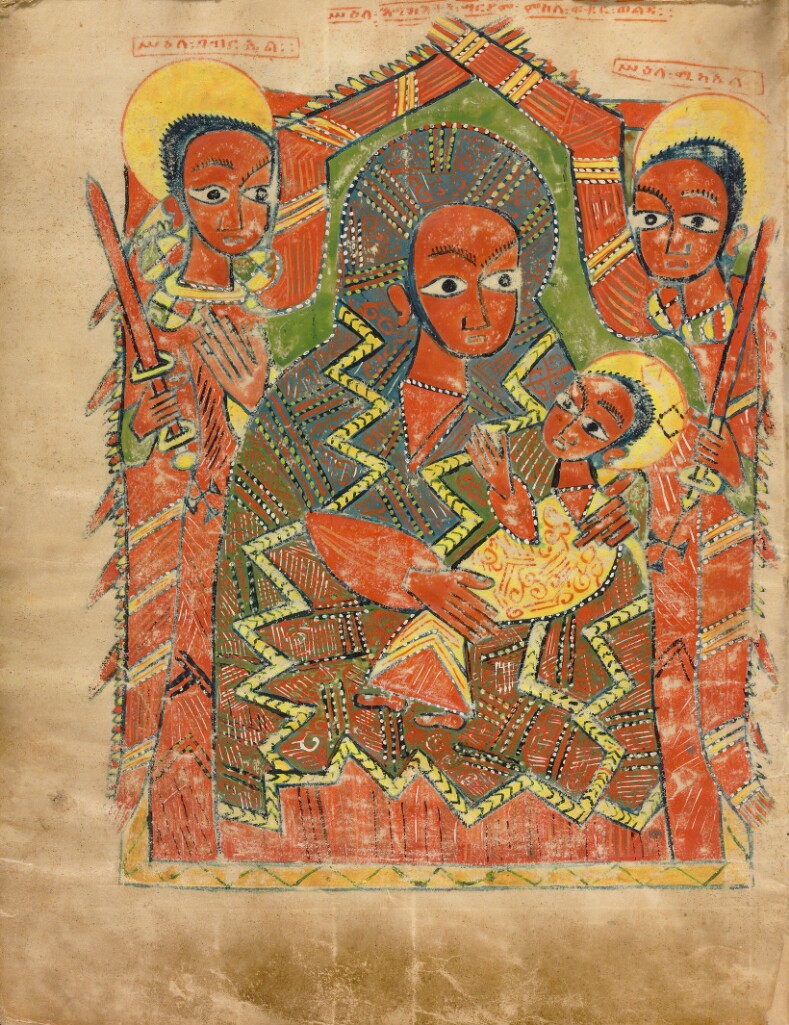

Theologies of the Global South are not only or even primarily about ethics. Even when ethical questions are not separated from theological reflection and they are often given explicit importance (questions of sexism, racism, and colonialism), these theologies are primarily systematic theology. It may change the way systematic theology is comprehended: new methods and sources—historical, ethnographic, artistic—can be included in systematic theological work. At the same time, pre-colonial and pre-Christian cultural elements may be induced to Christian systematic theology—not to create some odd and arbitrary combination but to make Christianity more understandable and legitimate to millions of people. For example, naming Jesus as an ancestor in African theologies emphasizes the deep relevance of community, family, and ancestors in African cultures.

This theological endeavor is both critical and constructive. It is critical in its understanding of theology as always contextual and involving history, which by and large has been a history of exclusion and legitimation of power. New theological subjects have appeared, asking new kinds of questions about the meaning of the Christian tradition and the ways it has been interpreted.

It is not only about academic theology but also about church institutions and grassroots activities. The articles in this issue of teologia.fi offer examples of all these levels.

Obviously, not all theology created in the Global South can be framed as contextual or liberationist. There are also differences between denominations. Even within contextual theologies, there are differences between Catholic, mainline Protestant, Orthodox, and Pentecostal interpretations. This diversity can be seen as a strength rather than a weakness. It is also partially a product of ecumenical work.

All this diversity can be found in the following short essays, which cover Africa, Latin America, and Asia—and, within them, a variety of themes. This special theme issue also testifies to how internationally oriented Finnish theological research is today.

Veikko Somerpuro

Veikko Somerpuro