Insights into African Pentecostal theology

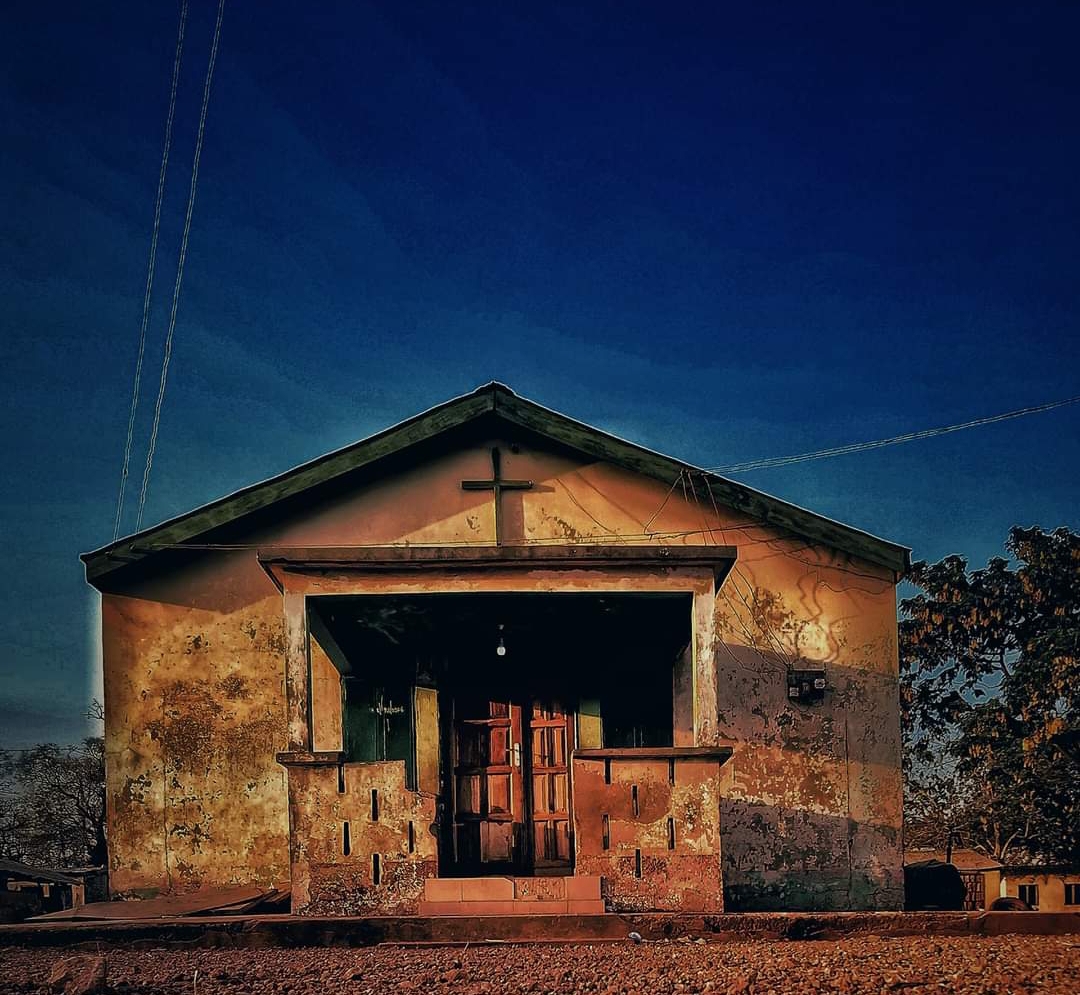

If you arrive at an average African Pentecostal Charismatic worship service, you will enjoy lively music, enthusiastic worshippers, powerful prayers, and dancing with the worshippers. Christianity sounds, smells, and feels like this in Africa, where Charismatic Pentecostalism is the fastest-growing form of Christianity.

Three trends in praxis and thinking

It is necessary to identify three different types of Pentecostalism present on the African continent today. These reflect the emergence of various forms of Pentecostalism in Africa. The first group can be identified as indigenous and independent Spirit-empowered movements, also called African Indigenous/Initiated Churches (AIC). These evolved from the activities of itinerant evangelists, who spoke in tongues, healed, and experienced trance in their ministry. They formed prayer movement that integrated practices which looked like occult activities when perceived by outsiders into Christian worship.

AIC communities were not originally accepted as Pentecostals because their theological interpretations or practices were not in line with the next group, the classical Pentecostal denominations that came from the West, especially after the Azusa Street Revival in the USA. Currently, academic studies identify AIC groups as one expression of Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity. The third group is the youngest, and it can be called neo-Pentecostals or Charismatic Churches. These were born of the revivals of the 1970s and 1980s, led by both Western evangelists and Africans inspired by their message. Stereotypical descriptions of these three sub-traditions regard the AIC as hospitals because of their main emphasis on healing, Classical Pentecostals as accentuating the need for holiness, and Charismatic Churches as proclaiming prosperity.

The method of theologizing

From a theological perspective, African Pentecostalism is highly diverse and multi-layered, with specific elements dependent on the geographic, cultural, and political context. Another challenge in finding explicit definitions comes from its non-textual character. It is expressed mainly in the form of prayers and songs during worship services, but it can also be discerned from everyday beliefs, practices, and affections. However, Clifton Clarke has formed an epistemological and descriptive definition, called the “call and response” methodology.

This call and response expresses an African cosmology in which everything is interconnected and interdependent. An Asante proverb from the Ghanaian tradition says, “I am because we are, and because we are, I am.” Call and response comes from the talking drums, which mediate messages back and forth, but also between gods, ancestors, and humanity. As a theological method, it describes the ongoing dialectic between the Holy Spirit (the call) and the experiences, both existential and other, of the people. Clarke identifies three different sources for the call: the Bible, African church history starting from antiquity, when Christianity arrived on the African continent with the first generation of believers, and the African religio-cultural context. The response is the reaction of the people. This initiates a relational and active bond with divinity, which is informed by the biblical message and everything that constructs a person’s life. Religion is not a body of knowledge or an ideology in the African context. It is an act of serving God or gods and responding to the call through dance, prayers, worship, and healing. The response is participatory and experiential rather than limited to words and texts.

Central beliefs

An African Pentecostal proclaims and performs based on the conviction that God is almighty and a powerful force, and there is no reality outside the confession “God is.” Therefore, religion is shared and experienced in all public arenas of life. God is a creator who has dominion over everything that exists, but this personal divine power is also a provider, a king, and an affectionate lover. These attributes are especially expressed in the songs of worshipping communities. To enter the African Pentecostal reality is to understand that sacred and secular are inseparable realities. This has required the gospel and theology to be contextualized in terms of this enchanted worldview, in which the forces of darkness are present in everyday life. Or better said, African Pentecostal communities have expressed their own theology according to their own needs and methods. Jesus is present to Africans in such a way that He answers the burning questions of the people whose identity has been marred by poverty, racism, colonialism, and many other forms of injustice. Therefore, the powers of darkness express themselves in reality, but the causality is always linked with spiritual forces that operate through traditional spirits, witchcraft, and demons. But God is holy and invincible, and this is the main confession of the Pentecostals.

The need for liberation has influenced the Christological emphasis prevalent in African Pentecostalism. Christ is the powerful liberator who has promised the fullness of life, prosperity, and health for His followers. Jesus saves from anything that threatens to rob one’s fullness of life: sickness, sorcery, poverty, barrenness, misfortune, war, locust invasions, epidemics – anything that can strike and destroy the community. Jesus is associated with the role of ancestors as a protector. Allan Anderson demonstrates how African Pentecostals have needed to clarify their relationship with ancestor veneration practices through diverse interpretations, ranging from cautious acceptance to full demonization. Clifton Clarke clarifies that the Pentecostal approach has the understanding that Christ is the Proto-Ancestor. However, Robert Agyarko prefers to use the term Nyamesofopreko, “God’s unique Priest”, as more suitable for Pentecostals. It is notable that the early post-colonial non-Pentecostal scholars’ inculturation of Christology, including such names such as John Mbiti, Charles Nyamiti and John Pobee, influenced the Pentecostal scholarly works, as remarked on by Clarke.

Despite this association with ancestors, Christ is considered above them in His infinite capability to conquer. Christus Victor, as named by Gustav Aulén, describes the identity of Jesus because of His works of healing, exorcising the possessed, and delivering the captives. Akan Pentecostal lyrics describe Jesus as The Hunter who goes to the deep forest and kills Sasabonsam, the evil spirit who prevents men from catching their prey. But an even more important role of Jesus is linked to His power to heal. The African holistic understanding of healing and its importance is linked to a multi-dimensional view of the universe and the interconnectedness of everything. Therefore, healing sicknesses touch on reality in both the physical and spiritual realms.

Religion is considered the means of manipulating forces in the spiritual realm. Therefore, spiritual warfare, both in practice and in theology, has gained a dominant place. For example, Pastor Abu Bako of the Rhema Foundation in Ghana has interpreted a Pauline concept of strongholds as altars. Those are an operational base from which spirits or deities function. Humans and any living creatures, lands, cities, organizations, communities or even activities can serve as these altars. This interpretation functions as a two-way street. Anything which has been at some point dedicated to a deity becomes a channel of unseen malevolent forces with an intent to influence and bind people through demonic oppression.

Anointing is understood as the presence of the Spirit in and on someone, and an anointed preacher, prophet, or pastor is seen as the possessor of the power of God

But a Spirit-filled Christian can function with the power of the Holy Spirit to judge these altars, break their power, and deliver the oppressed. In this context, being Spirit-filled means living under the empowerment and guidance of the Holy Spirit. The growth of healing and deliverance ministries is a sign of a need and the answer which the Charismatic Pentecostal interpretation of cosmology has offered.

Pneumatology is the crux of African Pentecostal theology, and the anointing of the Holy Spirit has a practical and kerygmatic importance. Baptism by the Holy Spirit has traditionally been a key doctrine in the Pentecostal tradition, and the theology of anointing is a continuation of that teaching. It has a stronger emphasis in Charismatic Churches but is present in all three groups. Anointing is understood as the presence of the Spirit in and on someone, and an anointed preacher, prophet, or pastor is seen as the possessor of the power of God. Anointing has multiple meanings; it breaks the power of strongholds, brings promotion, expansion, and greatness, and protects from the devil and any evil or malicious people. Anointing with oil is one example of a ritual that has great importance for communication of meaning and a worldview. It carries the symbols of both power and agency.

The Ghanaian Eastwood Anaba, an influential leader, uses anointing oil for six purposes: healing (spiritually and bodily), cleansing and awakening a person spiritually for repentance and regeneration, bringing the favour of God to someone, and bringing a prosperous life. This is linked closely to prosperity teachings, which have brought a shadow of disapproval on African Pentecostalism and its theology. It is important to recognize the influence of dispensationalism behind this theology of anointing, and the cry of Africans for their turn to have all the goodness and wealth they have seen taken away from their continent. African Pentecostals believe that now it is their time to receive the blessings of the kingdom of God and that this is the ongoing dispensation in the cosmic plan of God. Dispensationalism in general is a theological framework that informs the interpretation of God’s interaction with various peoples and divides history into dispensations as age periods. Commonly this system refers to Israel and eschatological expectations, and it is held as a mainstream theological understanding among Pentecostals. Professor Amos Yong, an Asian American Pentecostal scholar, provides an alternative interpretation of this oft-condemned prosperity gospel and argues that most Christians operate with a prosperity mentality but not with a prosperity gospel. The critics of prosperity theology are often wealthy Western theologians, mostly white males, who have never experienced poverty or any kind of oppression. The good news of Christianity has already brought to them the kind of prosperity that African Pentecostal communities are just dreaming about.

It is just about dawn…

African Pentecostalism is generating increasingly solid, and socially engaging academic theology. Alliance for Black Pentecostal Scholarship organized in cooperation with Pentecost University the 2nd Pan-African Pentecostal Symposium, in Accra, Ghana, in June 2024. Themes included studies on decolonization, question of gender, leadership and issues of injustice and poverty, all in the context of Pentecostal pneumatology. The African Pentecostal scholarship draws influence from various acknowledged and respected contextual theologies but reconstructs and incorporates those theological visions within a Pentecostal paradigm which has its own theological methodology and reflection, as illustrated above. This engenders a trend of academic theology which is then utilized to pastoral training in the largest denominations. However, how well it can affect the African Pentecostal reality remains to be seen.

Kirjoittaja

Suggested reading:

Clifton Clarke, Pentecostalism. Insights from Africa and the African Diaspora, Cascade Books, 2018

Global Renewal Christianity. Spirit-Empowered movements. Past, Present, and Future. Africa. Vol. 3, eds. Vinson Synan, Amos Yong and J. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, Charisma House 2016.

Karen Lauterbach, “Fakery and Wealth in African Charismatic Christianity: Moving beyond the Prosperity Gospel as Script”, in Faith in African Lived Christianity. Bridging Anthropological and Theological Perspectives, eds. K. Lauterbach and M. Vähäkangas, Brill 2020.

Pentecostalism in Africa. Presence and Impact of Pneumatic Christianity in Postcolonial Societies, ed. Martin Lindhardt, Brill 2014.

Amos Yong, “A Typology of Prosperity Theology: A Religious Economy of Global Renewal or a Renewal Economics”, in Pentecostal and Prosperity: The Socio-Economics of the Global Charismatic Movement, eds. K. Kattanasi and A. Yong, Palgrave, 2012.