Modimo: God as Mother in Tswana religious thought

This article concentrates on the image of God, Modimo, as Mother among the Tswana in Southern Africa. It deals with the traditional idea of creation also included in Tswana Christianity, which differs from the Western concept of creatio ex nihilo. It further discusses the role of women in a society that honours God as Mother.

Modimo

According to Tswana traditional thought, God is the Mother of all. Modimo is the root of everything that exists, the midwife to all that is living. Metaphorically she is described as the tender rain that softly wets the soil and makes it grow. For humans, it is possible to relate to God through her tender and lifegiving nature. At the same time, God – or the Supreme Being – is a mystery, terrifying and rough as the rain after lightning that beats the earth. You can also call her Rra (“father”) or selo (“thing”), but you can never understand this magnificent Power and the highness of this Most High. Simultaneously, God is bound to everything that exists. One can here talk about panentheism instead of pantheism or animism. Instead of these, God has shed something of her- or himself to everything that exists. The Christian Tswana, similar to followers of the traditional religion, also see Modimo as the Creator, Mothlodi.

However, some African philosophers, like Ghanaian Olusegun Oladibo and Kwasi Wiredu, claim that it is impossible to see traditional and Christian images of God in Africa as being similar. Rather, Christians – also in Botswana – have adopted the name of the traditional God when native translators suggested it for the first missionaries. Yet they base this claim on the idea that Christians believe in creation from nothing (ex nihilo), which is impossible according to traditional religious thought. One needs to acknowledge that the whole Tswana worldview was different than the missionaries’ European ideas, and this applied also to religious beliefs. However, if this argument is correct, it simultaneously nullifies the idea of God as a tender mother or midwife, which is highly valued also in Tswana Christianity. To understand this dilemma, one needs to understand the basis of the claim.

Tswana worldview

According to traditional Tswana thought, there is no dualistic distinction between spirit and matter, mind and body, or sacred and secular. There is not something beyond everything that exists. Instead, the seen and unseen worlds create one indivisible entity. The spiritual and bodily existence are bound together, and the spirit always has a spatial existence as well.

When Christians talk about creating something from nothing, ex nihilo, such an idea is impossible according to the Tswana worldview

Regarding the Tswana worldview, one can speak about spiritual monism, but not in the sense that the whole cosmos could be reduced to one basic substance (see Pöntinen 2013). Instead, the universe is furnished with different items, which were placed during creation in a certain order. This whole is then more than merely the sum of its separated fragments (holism). When Christians talk about creating something from nothing, ex nihilo, such an idea is impossible according to the Tswana worldview. Even the Most High cannot exist in nothingness.

Source of life

According to traditional religious thinking, Modimo is the source of life, the mother of everything, who nurtures all creation. Gabriel Setiloane, a Tswana theologian under apartheid in South Africa, explains this idea by stating that Modimo continuously creates both herself and all her manifestations. In other words, Modimo as Mother gives birth to all life continuously. Modimo is seen as Life itself, which pours out life to oneself and everything that exists. This idea presents Modimo as the Creator, who creates life from herself, not from nothingness. It also explains the idea of time, which among the Tswana has a clear existential dimension, underlining the present moment and its importance as a step to the future. Life is a precious gift from God to be perceived with two hands and enjoyed. The life in every breath we take is dependent on God to be used with thankfulness, here and now.

Women and society

This idea of God as Mother reflects the Tswana social life. According to anthropologists Jean and John Comaroff, Batswana (Tswana people) traditionally built both an agnatic and a matrilateral society, meaning that even if relations to the father’s family were seen as primary with regard to property and status, the ties to the mother’s kinship were closer and characterized by support and solidarity. Both sexes were also traditionally important in decision-making. Even if communal arenas were monopolized by men, the most foundational spaces for making decisions were the houses of the rulers’ mothers or maternal relatives. It was also possible for women to be traditional healers or herbalists, even if in social life the chiefs were always men.

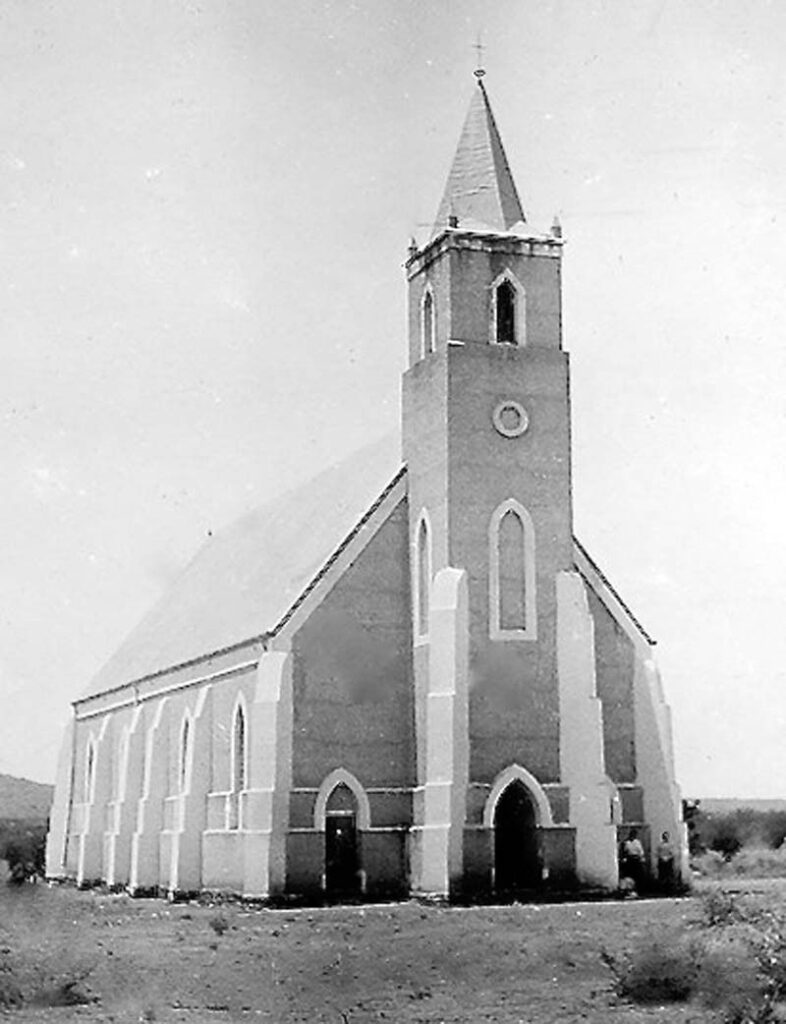

This has meant that in contemporary Southern Africa, women can be leaders of independent churches as well as men. It has also influenced Tswana Lutheranism. When the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Botswana decided to open ordination to female pastors in 1995, the vote was unanimous, even if some Western missionaries strongly spoke against it. On the contrary from European religious arenas, women are noted as religious actors. It has been explained that women are closer to Life and the Creator herself, because they are able to give birth.

Throughout history, however, women among the Tswana have also suffered from male dominance in decision-making regarding social norms. Bearing in mind the closeness of women to Life itself, we can take a widow, for example. The mourning period of a widow has traditionally been much longer and harder than that of a widower, so that death cannot pull women to die together with their former husbands. These negative and painful myths and norms, among others which have complicated women’s lives, are hardly made by the wisdom of women themselves. Rather, the women have been made to sustain the future of the tribe and confirm forthcoming childbirth and childcare in the villages.

It has been said that even if religious beliefs have supported female status and motherhood is highly respected, controversial norms and customs have been made. Like in most societies, women have had to struggle for their human rights, regardless of whether they have children or not. In this connection, it is worth noting that among the churches (e.g. the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Botswana), a lot of work has been done by local bishops, pastors, and laypeople to change the subordinative myths and norms, so that the beauty of beliefs and religious thought could be seen on a practical level and not only in religious arenas. Thus, Modimo is the mother of all.

Kirjoittaja

Literature

Amanze, James: African Traditional Religions and Culture in Botswana. A Comprehensive Textbook. Gaborone: Pula Press, 2002.

Comaroff, John & Comaroff, Jean: Of Revelation and Revolution. Christianity, Colonialism, and Consciousness in Soth Africa. Vol. I. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Oduyoye, Mercy Amba & Kanyoro, Musimbi R.A. (eds.): The will to Arise. Women, Tradition, and the Church in Africa. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1992.

Oladipo, Olusegun: “Religion in African Culture: Some Conceptual Issues.” In A companion to African Philosophy, ed. Kwasi Wiredu. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. 355–373, 2006.

Phiri, Isabel Apawo & Nadar, Sarojini (eds.): African Women, Religion, and Health. Essys in Honor of Mercy Amba Ewudziwa Oduyoye. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2006.

Pöntinen, Mari-Anna: African Theology as Liberating Wisdom. Celebrating Life and Harmony in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Botswana. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Setiloane, Gabriel 1976 The Image of God among the Sotho-Tswana. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema.

Wiredu, Kwasi: “Toward Decolonizing African Philosophy and Religion.” In Inculturation and Postcolonial Discourse in African Theology, ed. Edward P. Antonio. New York: Peter Land Publishing, 291–331, 2006.